Story of Hyperbolicity: a journey from geometry to solvability of word problems in non-technical terms

The word 'hyperbolic' is fascinating. What does it even mean? Like many other words in mathematical science, its meaning has evolved over time. In this article, in layman's language, we will take a tour of hyperbolicity through geometry, algebra and their wonderful reunion. No more than middle school mathematics is needed to carefully follow this story.

What is a hyperbolic space?

In the context of geometry, 'hyperbolicity' had a very specific meaning.

Consider a straight line L and a point P outside the straight line. How many lines can you draw through P that will never meet L (that is parallel to L)? If you are drawing this on a piece of paper then the answer is 1.

However it is possible to think about spaces where the answer is 0 (can you think of one such space? You know it for sure!)

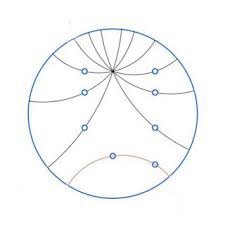

Yet another leap of reasoning will take you to another type of space where the answer is infinity. That is, given a line L and point P outside the line L, we can draw infinitely many lines through P parallel to L.

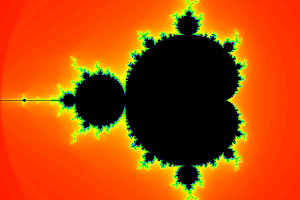

This type of space, however hard it is to imagine, theoretically exists. Such spaces are called hyperbolic spaces and this property (of having infinitely many parallel lines) is called hyperbolicity.

The way I think about it is, the space itself 'bends away' too quickly thus making a tonne of lines on it to bend away from the given line L. This sort of 'imagination' has its problems. In fact, a theorem of Hilbert roughly says, that such a space cannot be 'imagined' using our intuition of three dimensional space.

This meaning of hyperbolicity was conceived in 1830s by Gauss and later by Bolyai and Lobachevsky. But that was just the starting point of the journey of the word 'hyperbolicity'.

What are groups and how Dehn studied them?

About 70 years later, Dehn used the (evolved) strategy of hyperbolicity in a completely new context: to solve word problems in certain groups. Actually Gromov 'uncovered' this strategy embedded in Dehn's methods about another 70 years later. Notice that I mentioned 'hyperbolicity' as a strategy for solving problems instead of a concept. The meaning of this will be clear shortly.

A group is basically a set where you can combine (add) elements to create a new element of the same set. You could also substract one element from another. Though I am saying 'add', this operation can be some other rule of combination.

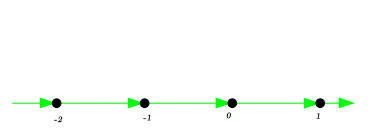

For example, the set of integers can be regarded as a group. In this 'set' one can 'add' two integers to get another integer.

In any group, we can specify an important subset S called 'generators' of the group. The generators, 'generate' the group, in the sense, you may repeatedly combine the generators to create all the elements of the set. For example, in the group of integers, {1, -1} is a set of generators.

Groups are important for a variety of reasons. They are among the most elementary algebraic structures that one can study (elementary does not mean 'simple'; group theorists know that even simple groups may not be 'simple''!

Another reason might be this: groups are used to model symmetries of objects. Since symmetries are important in physics and in many other sciences, therefore groups are important.

At any rate, given a group (a set) G, we can create 'words'. Here we are thinking about elements of the set G as 'letters'. One can combine (or add) several letters to form a new element of the same group. This combination of several letters is referred to as a 'word' which is also an element of G.

Word problem for a group

How do we tell if two words (created by combining letters) represent the same element of the group or not? This is known as the word problem of a group. It is, in general, very hard to figure this out.

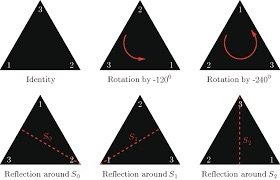

Here is an example. Consider the set of symmetries of an equilateral triangle: three reflections (about each median) and three rotations (0, 120, 240 degrees) about the centroid. Lets write the elements as {R1, R2, R3, Rot1, Rot2, Rot3}. They form a group. You can check this. For example combining any two elements this set, you will get another element of the same set.

You can actually combine two symmetries. Lets use * instead of 'add' for this sort of rule of combination of group elements.

For example R1*Rot2 means: first do a rotation by 120 degrees about centroid and the do a reflection about the first median. In this way, you can combine several elements to create a 'word'. But that word is again an element of the group (as combining elements of a group, by definition, gives another element of a group). In fact the same element can be written in many ways (in many words).

- R1*R1 = Rot1 as two times reflection brings the triangle back to its original position which is same as Rot1 (that is rotating by 0 degrees).

- Rot2*Rot2*Rot2 = Rot1 as thrice rotating by 120 degrees is rotating by 360 degrees which is same as rotating by 0 degrees.

- Hence the same element Rot1 is represented by two different words

Now lets write down two weird looking words:

Word1 = R1*Rot1*R2*R1*Rot1*R2*R1*Rot1*R2

Word1 = R3*Rot1*R2*R1*Rot1*R3

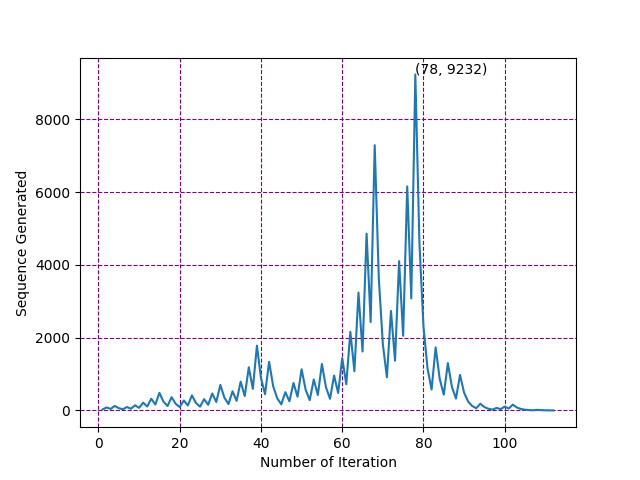

Do Word1 and Word2, represent the same element of the group? As I mentioned before, this is hard to check in general. However for certain types of groups, there are short algorithms to check this.

Group of Loops

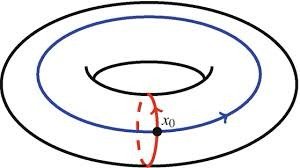

There is an important class of groups that was studied by Dehn. This class, for the sake of simplicity, is known as group of loops. Here is how you can think about it.

Given a space X, fix a point P in X and draw all loops starting and ending at P. This set (after doing some stuff) can be regarded as group. For example you can combine two loops by simply travelling along the first one first and then the second one.

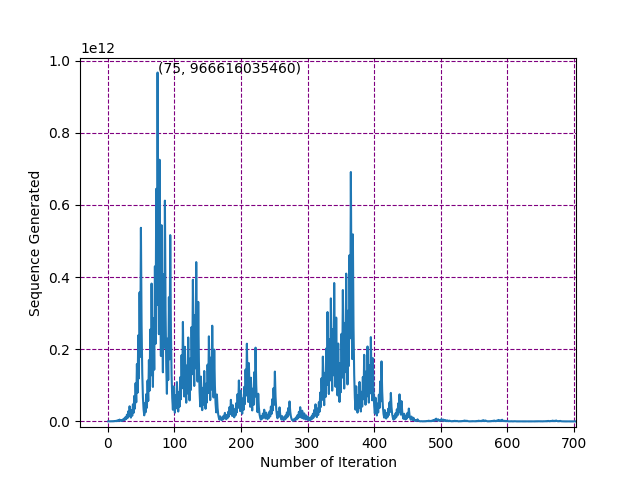

For certain types of spaces, these Group of Loops has a beautiful property called D- hyperbolicity. These groups have a solvable word problem. That is, given two words using letters of the group, you can check if they represent the same element of the group using an algorithm (that does the job in a 'small' amount of time.)

What is D-hyperbolicity?

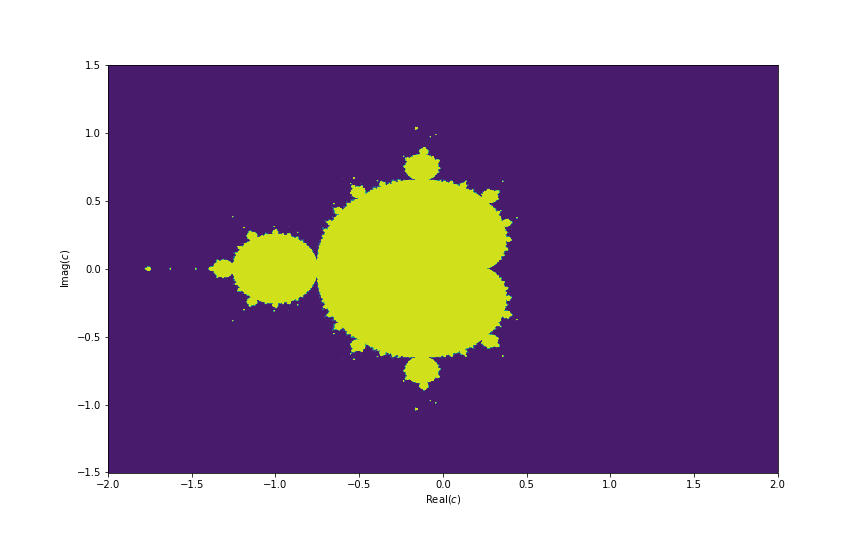

To understand the notion of D-hyperbolicity one should think of a group (a set of elements whose members can be combined to produce other members of the same set) as dots and segments. Represent each element of the group by a dot (make sure to label it the name of the group member). Join two dots g1 and g2 if g2 - g1 is a generator of the group G.

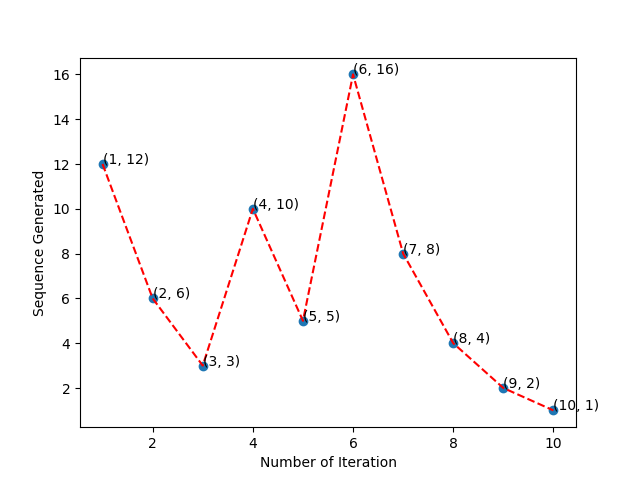

This creates a 'Cayley graph' of the group G. It contains bunch of dots and line segments known as edges. For example the Cayley graph of the group of integers with respect to the generating set {1, -1} looks like a straight line.

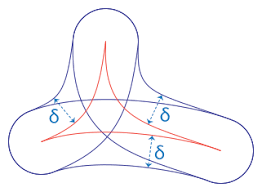

You can draw triangles on the Cayley Graph. To do that, pick three points A, B, C in the graph. Suppose each edge is 1 unit long. Then you can find paths (possibly consisting of several edges) joining A to B, B to C, and C to A. Some of these paths can be long winding. However some of them can be 'as small as possible. These shortest possible paths are known as geodesics. We can form a triangle ABC inside the graph by choosing geodesic paths in the graph connecting AB, BC and CA.

What Dehn found is interesting. Let G be a group and S be a generating set of the group. Let C be the Cayley graph of G. Suppose there their exists a magic number D, such that whenever you draw a triangle (having geodesic sides), any point on AC is within D unit distance from some point in AB or BC.

It does not matter how big the triangle is. The same magic number D must work for it.

This clearly does not happen in a piece of paper. Lets say you are guessing D = 5 (for flat piece of paper). But then you can create a large enough right triangle such that the midpoint of the hypotenuse is more than 5 units away from both the legs of the right triangle. In fact, from the stand point of geometry, a magic number D can only exists for hyperbolic spaces! This is that hyperbolicity that we discussed a while ago.

Dehn found that if such a magic number D exists for a Cayley Graph of a group , then the word problem for that group is solvable. This is a remarkable point where geometry meets algebra through hyperbolicity!

Subsequently, all spaces, where such a magic number D exists, are known as D-hyperbolic spaces. This considerably expanded the meaning of hyperbolicity and led to the rise of geometric group theory in the later part of 20th century.